Photographs for Tim

It’s now over a year since Tim’s passing. There is this story I need to tell:

On a cold, grey Saturday in December 2022, I took the metro to the other side of Paris to meet Tim’s friend, Jorge. Tim and Jorge met when Tim was studying in Paris. When Tim’s cancer returned, Jorge went to North Carolina to see Tim and his family. When he was there, Tim gave Jorge several rolls of bulk film to bring to back to Paris for me.

Jorge and I met up in a tiny café near where he worked. Soon after meeting, I realised that I had already seen his photographs: Tim had published them in Leicaphilia. You remember them, I am sure, in particular the guy with the mask on his head with two round eye-holes. Fantastic and mysterious and funny. On the cold winter morning, Jorge and I talked for maybe an hour or two about photography and many other things. I showed him a few of my own photographs on my telephone. “I don’t know,” he said, “but I think you need to get closer”. Looking at my photographs, I would have to agree. At the end, it was almost lunchtime, we parted company and Jorge handed me over three black bags on which were written ‘TMAX’ and ‘Kentmere’ on yellowing masking tape. Tim had said to me a few months previously: “This should keep you in film for a while” and indeed it seemed to be a lot. A quick calculation suggested that it was around 60 rolls of 36 exposures each. But it was bulk film, not already rolled into cartridges. I had never rolled bulk film into cassettes before.

Back on the other side of Paris, I went searching on the internet for a bulk roller and film cartridges, although I knew that at first I could just re-use a few of the old cassettes from film I was currently shooting. After developing and printing my own films for almost ten years now, bulk rolling was the ”final frontier”: something I had yet to try (there is still one thing left, I guess: mixing your own film developer from scratch. Not ready to go there yet). It was almost impossible to find good-quality metal cassettes: eventually, I tracked down an ebayer in … Kyiv, Ukraine. At one point many cameras were made there, and I supppose there must be mountains of film cassettes still lying around. The cartridges arrived early in the new year, and I couldn’t imagine the environment they must have come from. I did try loading one cassette without the bulk loader, in the darkroom at the Observatory. In the darkness, I spooled out what (I thought) was the right amount of film and prepared to put into the cassette. At that moment, the whole darkroom lit up. A notification on my telephone. Luckily, the light from the screen was partially blocked by my body and the film was undamaged.

By the end of December, I had rolled my first cassettes of Tim’s film. I did what I always do: I went for a walk around town and took photographs in the grey, shadowless winter light. This flat light is perfect for photography: no need to change any settings on the camera. But when I developed and scanned the first rolls them, I was disappointed to see the streets and buildings of Paris under a heavy curtain of grain. But I soon realised: this was obviously a message from Tim. On Leicaphilia he wrote (I am sure) thousands of words about the nature of film grain and how it was (mostly) different from electronic noise captured by digital detectors. Tim loved grain, and his images were bathed in it. Some of it real, some of it cooked up with software. I was not expecting TMAX (known to be a fine-grained film) to look like this, but perhaps the rolls had been too long in Tim’s freezer. I tried a few different developers (including one Tim sent me just before he died), but the grain remained. Obviously, this was Tim’s plan. It’s a message, it’s a message, I repeated to myself.

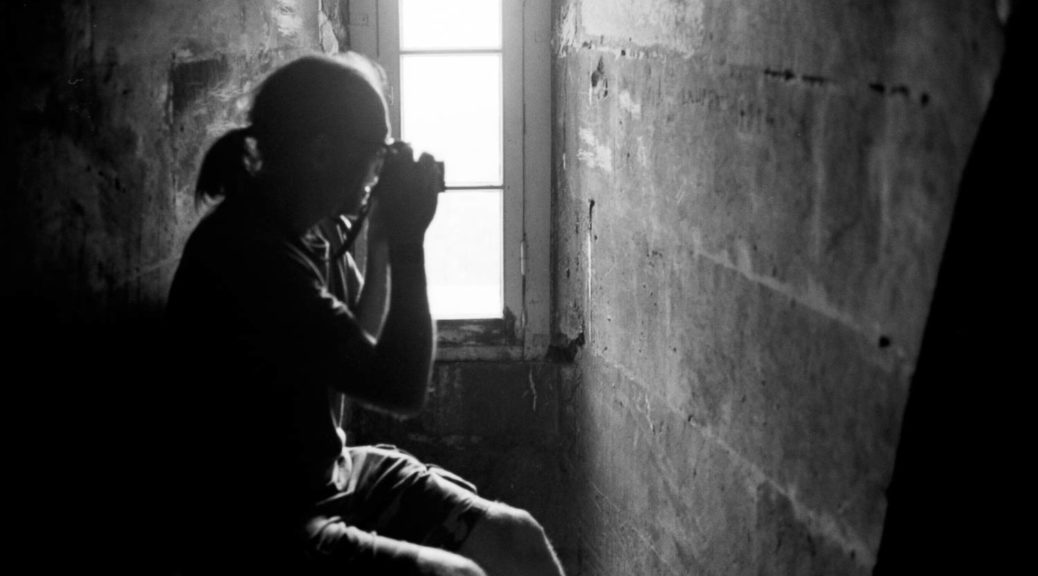

Soon, walking around with those rolls of film in my camera, I felt different. To start with, I knew that perhaps I shouldn’t care too much about getting the exposure or focus exactly right: with so much more grain, such considerations were secondary. I felt I had essentially a limitless amount of film, so perhaps I could take more photographs and be less careful? Because being careful doesn’t always lead to good photographs. Over the past few years, I’d see something, stop walking, take a photograph, then walk on. Time to try something different. I took off the 50mm lens and put on the small compact skopar 35mm lens, actually the first lens I bought with my M6 in 2015, and (I knew) a favourite of Tim’s. I decided to take this film with me on a few of my 2023 trips. The risk was that the images be lost to waves of grain didn’t bother me. When I came back from a trip to North America, on the scans I saw the Niagra Falls through a curtain of static and mist. It was fine.

I went to Ireland and the green hills dissolved under a grainy torrent. Looking at the scans, I realised it didn’t look so bad.

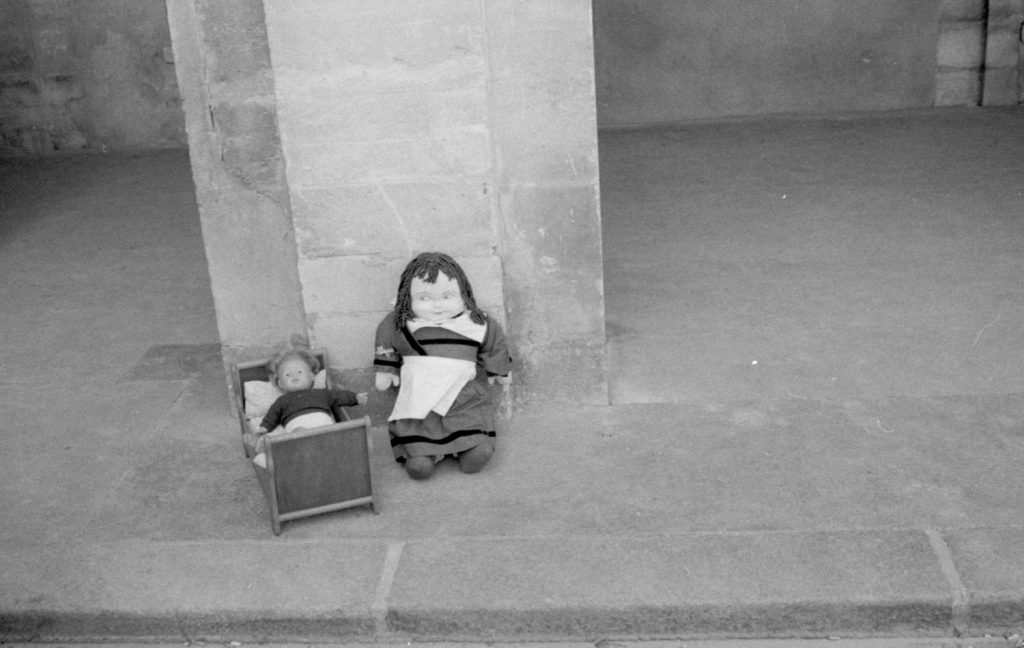

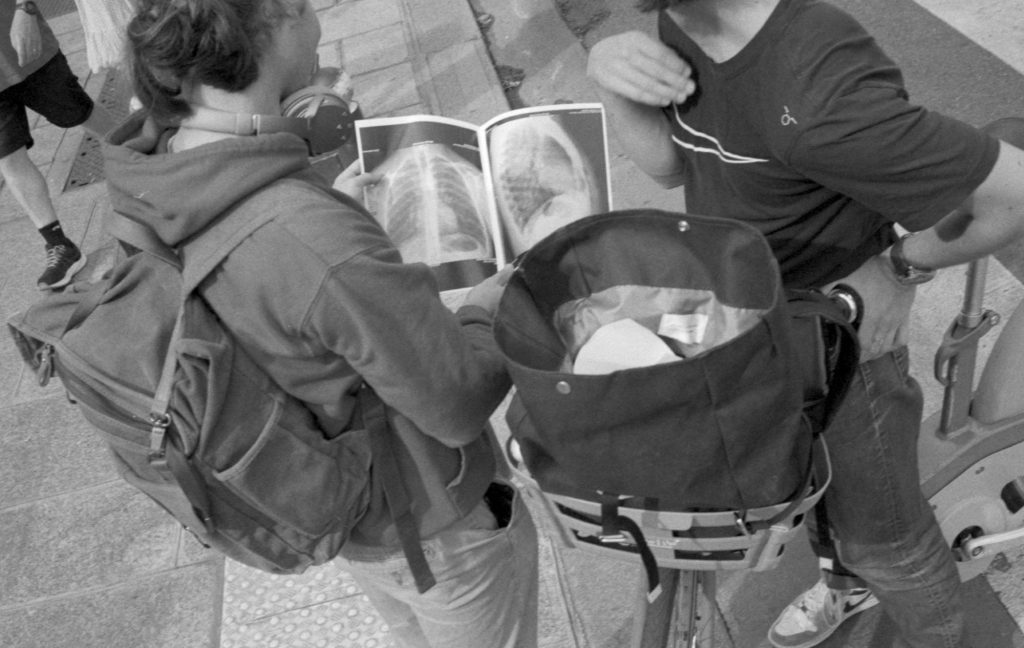

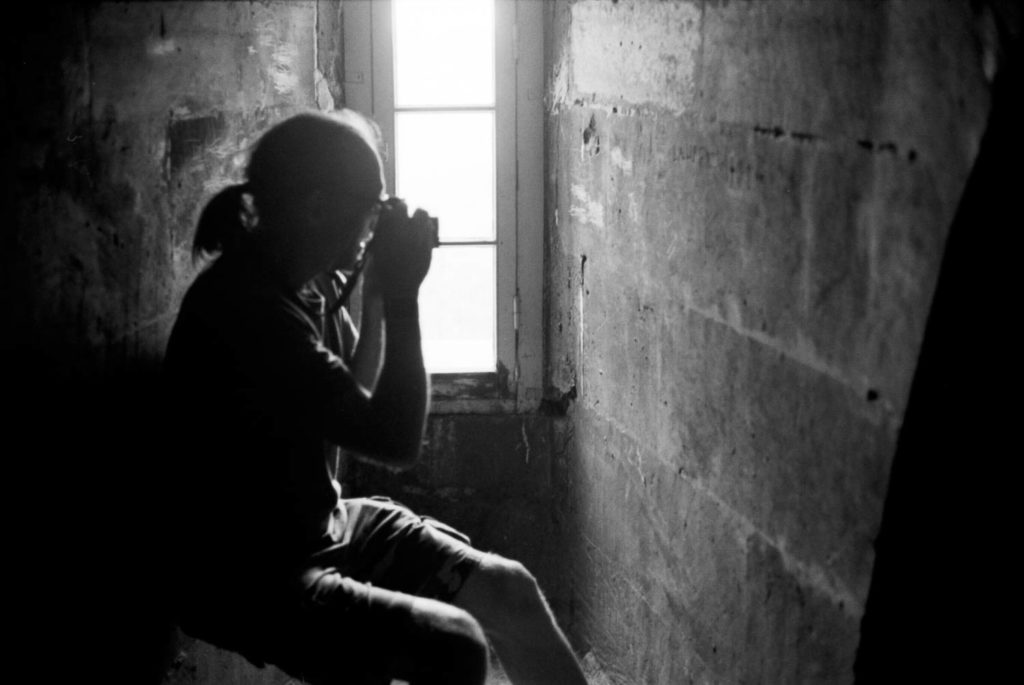

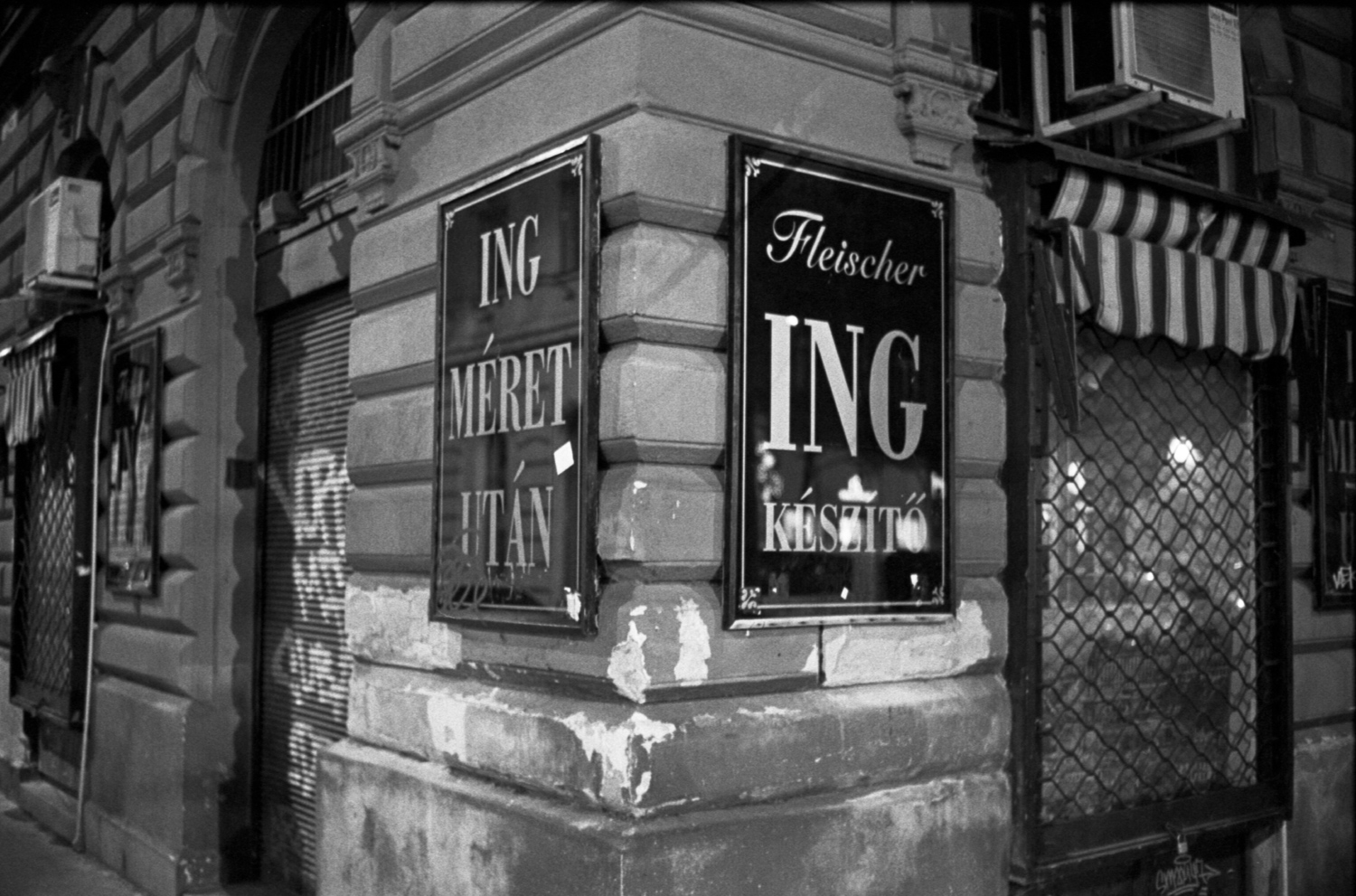

Euclid launched in July, and I was in Paris almost all of July and August. There are quite a few stories to tell about the first images from Euclid and how not everything worked out exactly as we expected immediately. Everyone working on the project in those days was under enormous pressure to understand the satellite and what was happening out in space. But on the weekends I was happy to take my camera filled with rolls of Tim’s film and walk for miles around town in the baking heat, taking many pictures. Shutter set to 1/250, don’t stop, click. I got close enough. I saw some weird stuff.

I had my zones of predilection. In the Marais you could see all sorts of things if you walked around enough. It is hard taking pictures in Paris: everything here has been worn down, photographed millions of times.

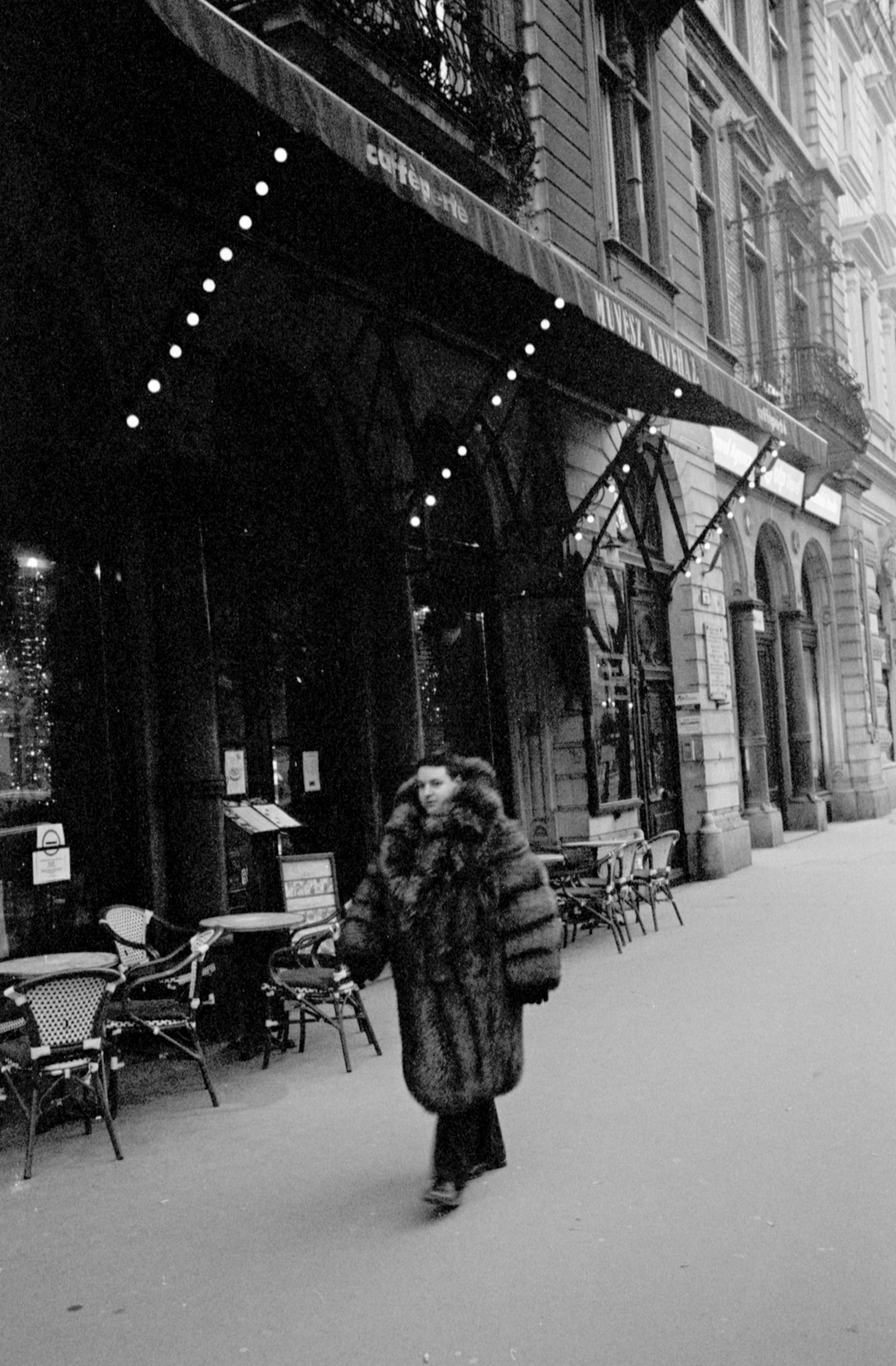

Soon enough, it was winter again, and the gray days were back. Before I knew it, I had my last roll of film in the camera. I was walking across the street. There was some kind of weird glitch. 70 years slipped away. And then it was the last exposure in the roll.

By the end of the year, I had around 30 or so interesting photographs that maybe I wouldn’t have taken if Tim hadn’t sent me that film. They are here. Thanks, Tim!